“Pour vivre heureux, il faut vivre caché”

Until he lost $20 billion in two days, as late as last month, Bill Hwang was the greatest unknown trader on Wall Street. Bloomberg Businessweek describes him as “largely unknown outside a small circle: fellow churchgoers and former hedge fund colleagues, as well as a handful of bankers.” Hwang is not the guy who needed to appear on CNBC to boost his profile because he wanted no public profile. For Hwang, it is the age-old approach to life and business (with good reasons as a minority in America), best codified by the French mind: pour vivre heureux, il faut vivre caché – to live happily, you must live hidden.

In an April 8, 2021 article, “The fast rise and even faster fall of a trader who bet big with borrowed money,” Bloomberg Businessweek’s Erik Schatzker, Sridhar Natarajan, Katherine Burton, and Hema Parmar did a deep dive on pieces of the puzzle of Hwang’s case. They described Hwang (pre-$20 billion loss) as “the greatest trader you’d never heard of.”

So, after nearly two decades as a hedge fund “whale” in the shadows, in the last week of March 2021, boom! It all came crashing down. In a matter of two days, Bill Hwang lost over $20 billion – and counting. Unlike some of the big frauds and criminal schemes that have cost Wall Street and the public trillions of dollars over the years, so far there is no evidence that Hwang committed outright fraud, which makes it even worse.

The man lost $20 billion in two days – LEGALLY! There should be a law against that. Unlike energy, which changes form but can never be destroyed, money (a few thous or mills) can be destroyed by burning it, tearing it up, flushing it down the toilet, or losing your laptop with your bitcoin account. But not $20 billion. You can only destroy $20 billion on Wall Street. For this reason, I think poor Bill Hwang (formerly rich Bill Hwang) will have a hard time staying out of prison because you don’t lose $20 billion in America and not go to the big house.

The facts mentioned are based on the Bloomberg Businessweek reporting; the analysis and commentary in this post are mine own.

A Modern-day Icarus

Roman poets Ovid and Virgil, along with Greek Historian Diodorus of Sicily, were among those who made the story of Daedalus and his son Icarus famous. It’s a tale that plays itself out regularly in the contemporary political realm and in the global investment community. To escape imprisonment on the island of Crete, Icarus flew with artificial wings attached by wax. Cautioned that flying too low would risk drowning while too high (near the sun) would risk melting the wax and losing his wings. He nonetheless flew too close to the sun, melting the wax, losing his wings, and falling into the sea to drown.

In real-life cases, modern-day Icaruses tend to be less about their failure to heed advice to be measured in their actions. Instead, they repeatedly bear out the same irony: waxed wingers are the ones who set out to be the highest flyers. You can almost predict a melting that will lead to the crash and burn or the crash and drown. Hubris in the face of vulnerability is an abiding trait. Once equipped with wax-attached wings, it becomes an abiding instinct to temp the sun.

Bill Hwang was a modern-day Icarus. He not only tempted the sun but moved around with his own fire and sticks of dynamite. He defied nature’s principal law of randomness, taking refuge in hubristic Christian dogmas – all while a high-roller better in a sinners casino.

The Paradox of Bill Hwang

Bill Hwang was a living paradox: a modest man who lived a low-keyed and humble life, yet a Wall Street gambler who placed out-sized bets like a drunken high roller in a Las Vegas casino. He was loaded, yet he had none of the usual trappings of a hedge fund manager.

Bill Hwang had no expensive sports cars, no private jets, no lavish mansion in Greenwich Connecticut, no Manhattan penthouse overlooking Central Park, no chalet in Switzerland, no Paris apartment. Instead, Hwang drives a Hyundai SUV and owns a suburban New Jersey home. Modesty defined his personal life. In a 2019 video recorded at New Jersey’s Metro Community Church, Hwang said, “I grew up in a pastor’s family. We were poor. I confess to you; I could not live very poorly. But I live a few notches below where I could live.”

Bill Hwang was a devoted churchman who gave generously, claiming to divide his time evenly among three passions: his family, his business, and his charity, the Grace & Mercy Foundation – a $500m foundation that investigators will undoubtedly be scrutinizing in the next few months. In a 2019 video for his foundation, he said, “I try to invest according to the word of God and the power of the Holy Spirit… In a way, it’s a fearless way to invest. I am not afraid of death or money.”

The Vicar of Wall Street

Those are hardly the words you would expect to hear from a fund manager playing with billions of dollars of other people’s money but it points Bill Hwang’s hubris, perfected in provincial Christianity.

As evangelism (belief-based) bears no resemblance to analytical reason, hearing a man say that he tries “to invest according to the word of God and the power of the Holy Spirit,” should have inspired fear and loathing, as far as investors are concerned. Taking investment decisions based on the word of God and the power of the Holy Spirit? Well, most investors might have preferred computer-based models.

While most did not know this side of Bill Hwang, some did. In February 2016, a group affiliated with New York’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church – the Financial Services Ministry that connects Christians in finance – included Bill Hwang’s name on an invitation emailed to members. It advertised a weekend retreat at the Princeton Theological Seminary “to explore the Gospel’s power to transform who we are and what we have been called to do in this industry.” The main event was a Saturday dinner with three of the ministry’s advisers: ARK Investments startup money manager Cathie Wood, former Merrill Lynch director Paul Gojkovich, and Bill Hwang.

Wood and Hwang shared a similar trajectory for a time. As Archegos piled up winning trades in private, Wood became a public investing sensation. Her flagship exchange-traded fund, a technology-heavy portfolio open to any retail investor, wowed the market with a 148% return in 2020. Hwang invested with Wood, and, according to one of his former employees, Archegos and ARK collaborated on industry research.

Pious Humility Meets Wall Street Casino

Pious humility reconciled with casino-style high stakes betting high above Central Park, on the 38th floor of 888 Seventh Ave. On one side was Hwang’s Grace & Mercy Foundation, and on the other, his Archegos Capital Management. Bill Hwang did not have to walk far for the Lord’s inspiration to invest or to do God’s work with the fruits of ungodly and risky bets.

Bill Hwang’s reconciliation of faith with finance was on full display at the seminary retreat. One person who attended recalls discussing Archegos Capital Management’s portfolio with Hwang. Archegos then included Amazon.com, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Netflix. Hwang explained that cutting-edge companies were doing “divine work” by advancing society. Archegos had also owned Google’s parent company Alphabet Inc.’s stock for five years, so he told congregants in his 2019 appearance at Metro Community that God loved Alphabet Inc.’s Google because it provided “the best information to everybody.”

Elsewhere, in a video, invoking the multiple references to just weights and balances in the Old Testament, Hwang said, “God also cares about fair price, because the scripture said God hates wrong scales. My company does a little bit, our part, bringing a fair price to Google stock. Is it important to God? Absolutely.”

While it would be tempting to see Bill Hwang, as yet another in American’s long line of prosperity-preaching charlatans, from Norman Vincent Peele onward, Hwang is seemingly a genuine man of faith from a family of Korean Christians. Perfecting a certain provincial protestant bona fides that further legitimized him outside of Wall Street was but one side of him.

He genuinely sought to use his money to do good. His Grace & Mercy Foundation gave millions of dollars a year, primarily to Christian causes. Although little known to Wall Street, Hwang has been a pillar of his church community. Among its biggest beneficiaries, the Fuller Foundation and Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif., and Washington’s Museum of the Bible. Others in New York include the Bowery Mission and the King’s College, a Christian liberal arts school.

Bill Hwang hosted three Scripture readings a week at his foundation offices in Midtown Manhattan—a 6:30 p.m. Monday, a 12:30 p.m. Wednesday lunch, and a 7 a.m. Friday breakfast. He also sponsored another at Metro Community Church. Between listening to scripture and reading himself, Hwang says he spends at least 90 hours each year digesting the entire Bible.

Hwang is closely involved with a group called Liberty in North Korea, or Link, that has helped about 1,300 North Koreans escaping the regime. “He doesn’t use God as a cover,” says Jensen Ko, a colleague at Archegos. “He lives that out.”

Underlying all of this, however, was a flawed Bill Hwang – a man who believed too much in himself, taking extensive risks with his own money and other people’s money.

Success Breeds Silence – Encourages Corruption

Success is the graveyard of the critic. It brooks neither opposition nor examination. Everyone is happy, everyone is quiet, even in doubts about methods. It’s the reason Ponzi and illegal trading schemes are neither rare exceptions nor at the periphery of Wall Street. They are at its core – as commonplace and recurrent as the seasons that appear with the earth’s rotation of the sun.

Bill Hwang’s Archegos Capital Management never showed up in the regulatory filings that disclose major public stock shareholders. Yet, Hwang was one of “the biggest of whales (dominant presence in the market), without ever breaking the surface.” This changed almost overnight in March 2021 when he lost all of $20 billion in just two days – the millennial version on Nick Leeson and a long line of others since. Let us recall the recurring pattern.

In 1995, Nick Leeson, a rising young derivatives trader at England’s Barings Bank‘s Singapore office, lost $1.3 billion of the bank’s money in risky derivatives and unauthorized derivatives trades. Leeson’s primarily traded arbitrage for Barings’ clients on the Nikkei 250 – the main Tokyo index.

It was a global story of the century – an almost unheard of loss resulting from inadequate internal control, a scandal on par with Match King Ivan Kreuger’s fraud in the 1930s. Venerable Barings, one of Britain’s oldest merchant banks, collapsed, and Leeson spent four years in a Singapore prison. In the years to follow, other hedge funds would implode in similar fraudulent fashions.

The following year, 1996, Sumitomo Corporation’s “copper king,” Yasuo Hamanaka, lost $1.8 billion in unauthorized copper trading and imprisoned for eight years. In 1998, John Meriwether and the Nobel geniuses who led Long-Term Capital Management famously led it to implosion after famously losing $4.6 billion.

“Ponzi King” Bernie Madoff imploded in 2008. He was later imprisoned for 150 years – more than twice the average African bush elephant’s lifetime. That same year, Societe Generale’s “computer genius” – trader Jérôme Kerviel decimated Neeson’s record trading loss by blowing through $8 billion and spent three years in prison.

In 2010, Britain’s Navinder Singh Sarao used an automated program to generate massive sell orders of E-mini S&P 500 futures contracts. This drove prices down and plunged the Dow Jones Industrial Average more than 1,000 points (about nine percent) within minutes – a “flash crash” that briefly wiped out nearly $1 trillion in market value.

Finally, in 2011, UBS’s British trader, Kweku Adoboli lost $2.2 billion – the largest trading loss in British banking. He was imprisoned for seven years

The Whale of Wall Street

Well, none of this is the case of Bill Hwang. While Hwang gambled big and risky, there’s no evidence yet that Archegos broke the law. Though, what Hwang has shown is that the law is broken. Bill Hwang was good at betting on stocks. He invested using fundamental analysis to find promising stocks, with which he built a highly concentrated portfolio.

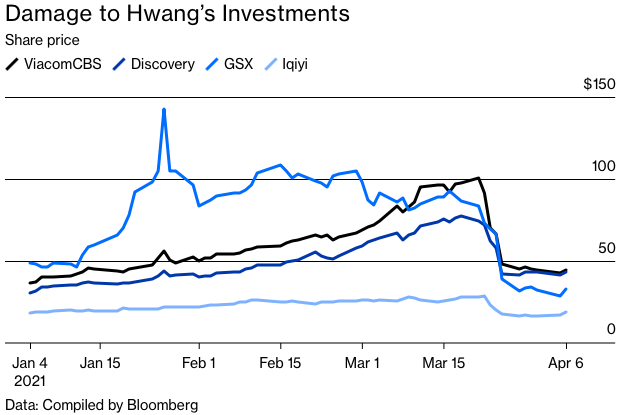

Hwang’s trading strategy was simple. There was no arbitrage on collateralized bundles of obscure financial contracts as in 2008’s sub-prime meltdown. His fund, Archegos Capital Management, placed most of the money it borrowed into a handful of stocks—among them, ViacomCBS, GSX Techedu, and Shopify.

No human being has ever been left licking their chops for a “do-over” like Bill Hwang. In 2013, after closing his hedge fund, Bill Hwang took over $200 million and made a fortune betting on stocks. At its peak, Hwang’s net worth briefly topped $30 billion. Up to March 2021, had he cashed out, he would have been sitting pretty atop Forbes’ global billionaire listing – with a cool liquid net worth of at least $20 billion. But Hwang didn’t. And by late March, in all of two short (or very long) days, his Archegos Capital Management suddenly imploded – distinguishing Bill Hwang as the only person in recorded history to have lost that much money so quickly.

Bill Hwang used derivative swaps that give an investor exposure to gains or losses in an underlying asset without owning it outright, which hid both his identity and the size of his positions. Even the firms that financed Hwang’s investments couldn’t see the big picture of his gambles.

On Friday, March 26, Archegos Capital Management defaulted on loans it used to build a $100 billion portfolio. When investors worldwide, many of whom were Hwang’s creditors, learned of the news, the first question was, “Who on earth is Bill Hwang?”

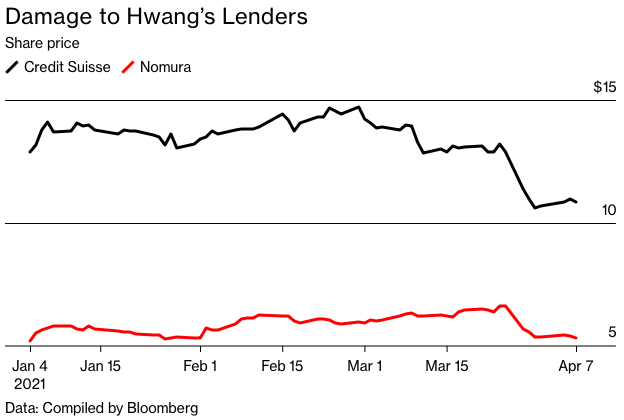

Hwang used borrowed money to multiply his bets fivefold. In terms of the markets, his default set off a wave of tornados. Its aftermath was a post-tornado calamity – time to assess the macabre trail of destruction. The bodies were now strewn all over Wall Street’s tornado alley, and the rush was on to minimize its impact. Banks dumped his holdings – decimating stock prices. Credit Suisse Group AG, one of Hwang’s lenders, lost $4.7 billion. Several top executives, including the head of investment banking, were immediate casualties – fired. Nomura Holdings Inc. loss will likely top $2 billion.

“The Tiger Club”

The former Sung Kook Hwang immigrated to the U.S. from South Korea in 1982 and took the English name, Bill. Raised by his widowed mother, he attended the University of California at Los Angeles and eventually earned an MBA at Carnegie Mellon University. In a videotaped business school reunion posted online in 2008, Bill Hwang recalled his one objective upon graduation: moving to New York. In 1996, after stints as a salesman at two securities firms, he landed an analyst’s job at Tiger Management. Bill Hwang became one of Julian Robertson’s “Tiger cubs.”

Fund manager Julian Robertson wasn’t exactly the Joe Exotic of the hedge fund business, but he was nonetheless a legend and a great mentor to the next generation. Robertson’s Tiger Management was one of the earliest prominent hedge funds. Many former Tiger employees went on to open their own shops.

Bill Hwang was now not only playing in the major leagues but playing in its top tier. At a reunion, Hwang remembered a key lesson his mentor, Julian Robertson, had taught him early on: learn how to live with losses. Tiger had lost $2 billion betting the wrong way against the Japanese yen, and “everyone was panicking.” According to Hwang, Robertson came into the room and said, “Guys, calm down. It’s only work. We do our best.”

That was likely the point of departure to high-stakes Wall Street gambling. Learning to live with losses could involve positive coping strategies, but it could also be conditioning a type of psychopathy within us – losing the fear of consequences for our actions. This can be exhilarating and vicious at the same time because the exhilaration then feeds the vicious cycle of fearlessness.

As a flight student in college, I tended to tense up while holding the airplane’s yoke. One instructor would always remind me of the same thing: “Paul, you have to learn to lose the fear, and in six months, you’ll be barnstorming.” He was correct. In no time, I was handling the airplane’s yoke like the steering wheel of my Mazda RX-7’s, in which I had racked up more than my share of speeding tickets. I had lost my fear of flying, just as I had lost the fear of speeding.

For Bill Hwang, learning to live with losses on Wall Street might have started with losing the fear of consequences. Risk aversion likely left the room at that time, unshackling and abandoning the protestant puritan to the whims of his true master.

Branching Out – Tiger Asia Management

Tiger Management shut down in 2001, and papa tiger Julian Robertson encouraged his “cubs,” including Bill Hwang, to start their funds, offering them the seed capital. Among fellow “Tiger cubs” who branched out to form some of the world’s most successful hedge funds were Andreas Halvorsen with Viking Global Investors, Philippe Laffont with Coatue Management, and Chase Coleman with Tiger Global Management.

Bill Hwang branched out with his own fund, Tiger Asia Management, which had about $10 billion in assets. In the early days, both Tiger Asia and Coleman’s Tiger Global were on the same floor of Julian Robertson’s Park Avenue offices. There were frequent collaborations between the two. Bill Hwang and Coleman often lunched together to share views on the market. One former Tiger Asia employee remembers Hwang returning to the office after he and Coleman had decided against paring back some investments during a period of market volatility. According to the employee, Hwang said, “I think Chase and I are very similar. We need to go on the offense.”

Initially, Bill Hwang differentiated himself by investing only in Korean, Japanese, and Chinese companies that generated all of their revenue domestically. Former clients and colleagues say Hwang concentrated the Tiger Asia portfolio in a small number of stocks and levered it. Some of his 25 or so positions were longs (bets on rising prices), while he “shorted” others (bets on declining prices). But according to the former employee, Bill Hwang was secretive, often hiding vast holdings from his own analysts – a practice he continued years later at Archegos Capital Management.

In 2008, Tiger Asia was shorting Volkswagen AG when takeover speculation sent the shares soaring. The stock quadrupled in two days, and Bill Hwang had to close his position at a loss. He ended the year down 23%, and many investors pulled out, furious that an Asia-focused fund was gambling in European markets. This might have provided an insight (if anyone was looking) into Bill Hwang’s unrestrained propensities.

Then Bill Hwang breached the line between aggressive and illegal. In 2012, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission accused Tiger Asia of insider trading and manipulation in two Chinese bank stocks. The agency said Hwang “crossed the wall,” receiving confidential information about pending share offerings from the underwriting banks and then using it to reap illicit profits.

Bill Hwang settled that case without admitting or denying wrongdoing, and Tiger Asia pleaded guilty to wire fraud. In a 2016 talk in South Korea, Hwang told the story of his mother, then a missionary in Tijuana, Mexico, calling to ask about the penalties. When he said to her that the fines and disgorgements totaled more than $60 million, she replied, “Oh, dear. You did well, Sung Kook. Our America is going through a difficult time. Consider the amount you are paying as a tax.”

Hwang then closed his Tiger Asia Management fund. Yet despite this, he kept the Wall Street prime-brokerage departments that finance big investors on his hook. For his next venture, he received the billionaires’ treatment from brokerage firms – they extended him all the leverage he needed.

Archegos Capital Management

In 2013, Hwang started Archegos Capital Management as a family vehicle to manage his personal wealth. There were no outside investors, only his own money. Some saw it as a move for redemption after the SEC settlement. Others saw a risk-taking junkie acting out his natural impulses. Archegos became a lucrative client for the banks that eagerly lent him tons of money, unknowingly to shore up his casino-like gambling.

Sources say Bill Hwang’s investments in the first few years he ran Archegos included Amazon, Expedia Group – the travel-booking engine, and LinkedIn – the job-search site Microsoft acquired in 2016. A winning bet on Netflix Inc. netted Archegos close to $1 billion, one former colleague estimates. Hwang championed technological disruption, which millions of retail investors were beginning to embrace.

According to a former banker who helped oversee its account at his firm, by 2017, Archegos had about $4 billion capital. As with Bernie Madoff and countless others whose modus operandi was secrecy, Bill Hwang shared few financial details with his lenders. As with Madoff and many others, as long as the gravy train was running smoothly on the tracks, no one raised any red flags. According to a person familiar, Hwang’s leverage at the time was about the same as a typical hedge fund running a similar strategy, or two to two-and-a-half times.

Courting Risk

U.S. securities laws prevent individual investors from buying securities with more than 50% of the money borrowed on margin. But no such limits apply to hedge funds and family offices, which means Bill Hwang’s activities were exempt. People familiar with Archegos say the firm steadily ramped up its leverage. Initially, that meant about “2x,” or $1 million borrowed for every $1 million of capital. But by late March 2021, the leverage was 5x or more.

The risk inherent with picking stocks on the scale Bill Hwang operated scale is the hedging strategy. Sophisticated stock pickers reduce their risk by balancing (offsetting) long positions with shorts on similar names. That way, they make up some losses with profits if the market goes against their primary strategy.

One ex-banker recalls Archegos having a portfolio short. With “shorting,” you borrow shares and sell them, making money if the stock declines. In practice, it’s often hard to find enough shares or to borrow them cheaply. So, another way to hedge is a “portfolio short” – a broad bet against the entire stock market – often made through options or futures contracts on the S&P 500. This is relatively easy to execute, but the hedge will only work if the market drops.

Bill Hwang kept his banks in the dark by trading via swap agreements – a bank gives its client exposure to an underlying asset, such as a stock. But while the client gains or losses from any price changes, the bank is still the owner of the underlying asset, and it shows up in filings as the registered holder of the shares.

This is how Bill Hwang was able to amass huge positions so quietly. Likewise, because lenders only had details of their own dealings with him, they, too, couldn’t know that Hwang was adding on leverage in the same stocks via swaps with other banks. One example is ViacomCBS Inc. The largest holder of record – the Vanguard Group Inc. – had 59 million shares. But by late March, Hwang’s Archegos had exposure to tens of millions of shares of the media conglomerate via Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Credit Suisse, and Wells Fargo & Co.

In the past few years, Bill Hwang’s investments shifted from mainly tech companies to a more eclectic mix. Media conglomerates ViacomCBS and Discovery Inc. and at least four Chinese stocks: GSX Techedu, Baidu, Iqiyi, and Vipshop, became significant holdings.

While it’s impossible to know when Archegos made those swap trades, Hwang’s banks’ regulatory filings provide some clues. Starting in the second quarter of 2020, all the banks he dealt with became big holders of the stocks he bet on. Morgan Stanley went from 5.22 million shares of Vipshop Holdings Ltd. as of June 30 to 44.6 million by Dec. 31. Leverage played a growing role, and Hwang continued the trajectory, looking for more sources of leverage. He was gambling more and more with other people’s money.

According to people with direct knowledge of the matter, company compliance officials who looked suspiciously on Bill Hwang’s checkered past blocked repeated internal efforts to open an account for Archegos. Goldman Sachs had blacklisted Bill Hwang. But other banks, unbothered by his previous brush with the S.E.C. and Justice Department, continued to do business with him. Credit Suisse Group AG and Morgan Stanley have been doing business with Archegos for years. Now they are burned – siphoning through the carnage to get a handle on the full extent of their losses.

At the close of every trading day, Archegos would settle its swap accounts. If the total value of all positions in the account rose, the bank in question would pay Archegos cash. If the value fell, Archegos would have to put up more collateral, “post margin.” The fourth quarter of 2020 was a fruitful one for Bill Hwang. While the S&P 500 rose almost 12%, seven of the ten stocks Archegos was known to hold gained more than 30%, with Baidu, Vipshop Holdings Ltd, and Farfetch jumping at least 70%.

This made Archegos one of Wall Street’s most coveted clients. People familiar with the situation say it was paying prime brokers tens of millions of dollars a year in fees, possibly more than $100 million in total. As his swap accounts churned out cash, Bill Hwang kept accumulating extra capital to invest—and to leverage up. Goldman Sachs finally relented and jumped on the gravy train – signing on Archegos as a client in late 2020. Weeks later it all would end in a flash.

The Downfall

The week of March 22 saw the first in a cascade of events. Shortly after the 4 p.m. close of in New York trading that Monday, ViacomCBS, struggling to keep up with Apple TV, Disney+, Home Box Office, and Netflix, announced a $3 billion sale of stock and convertible debt. The company’s shares, propelled by Hwang’s buying, had tripled in four months. To executives in the ViacomCBS C-suite, raising money to invest in streaming made sense. Instead, the ViacomCBS‘ stock dropped 9% on Tuesday and 23% on Wednesday.

Bill Hwang’s bets had become combustible and unstable because his swap agreements were now widely jeopardized.

According to people with knowledge of the discussions, a few bankers pleaded with Hwang to sell shares. He would take losses, but he would survive and avoid default, they reasoned. But the resolute, fearless man of God (“I am not afraid of death or money”) refused. He had long lost the fear but had also forgotten Julian Robertson’s lesson: deal with loss!

That Thursday, Bill Hwang’s prime brokers held several emergency meetings. Swap professionals say he likely had borrowed roughly $85 million for every $20 million (over 4x) – investing $100 and setting aside $5 to post margin as needed. But Hwang’s massive portfolio tanked so fast that the losses engulfed his capital and the small buffer as well.

Mexican Standoff to a Bullrun

Bill Hwang’s lenders faced an evident dilemma: who might blink first. As the escaped lion approached a group of people in the woods, each looked at the other to see if one would break stance and bolt. If the stocks in Hwang’s swap accounts rebounded, everyone would be okay, but if even one bank flinched and started selling, they would all face exposure to plummeting prices. Credit Suisse Group AG, had the ability to immediately pull the plug and call a default but did the ‘honorable’ thing and stood its ground, deciding to wait – a fateful decision for which it is steering almost $5 billion in losses.

Credit Suisse Group AG had forgotten the old axiom: there is no honor among thieves – especially on Wall Street. Late that afternoon, Morgan Stanley stealthily blinked. Without a word to its fellow lenders, it made a preemptive move and quietly unloaded $5 billion of its Archegos holdings at a discount, mainly to a group of hedge funds. In Friday morning’s pre-trading, before the 9:30 a.m. New York open, Goldman Sachs started liquidating $6.6 billion in blocks of Baidu, Tencent Music Entertainment Group, and Vipshop Holdings Ltd. It followed with $3.9 billion of ViacomCBS, Discovery, Farfetch, Iqiyi, and GSX Techedu.

Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank AG, and Wells Fargo & Co had joined Morgan Stanley in liquidating at-risk Archegos and Archegos-affected positions. When the smoke cleared, they had escaped the Archegos fire sale unscathed. They had moved faster to sell, but it’s also possible that they had extended less leverage or demanded more margin coverage from Bill Hwang.

Scraps For Scavengers

As the ashes clear, Credit Suisse and Nomura Holdings Inc. seem to be the biggest casualties of Bill Hwang’s gambit. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc., another prime broker, has disclosed $300 million in likely losses. It is likely that they are any others who have decided to take the hit silently to save association and the public relations nightmare.

Bill Hwang is moderately ‘blessed’ that his implosion occurred when the country is busy fighting the biggest pandemic in a century and occupied with social and political upheaval. At any other time, there would be a public dragnet over Wall Street by now. As I mentioned earlier, there is no evidence that Hwang has done anything illegal – yet. But it is a sure bet that regulators are pouring over his past few years’ activities and of those who facilitated him. Bill Hwang will need the Lord now more than ever as he will undoubtedly spend the next few years fending off litigation from all corners – if not prison too.

In usual fashion, the public-relations must get ahead of the scandal. Doug Birdsall was Bill Hwang’s fellow attendant at Redeemer Presbyterian Church services. His nonprofit is a beneficiary of Hwang’s philanthropy. Unsurprisingly, Birdsall views Hwang’s quagmire with some optimism: “While people will be talking about how this guy had one of the biggest losses of wealth ever, he will not be defined by that. People will remember the kind of life that he lived, the character that he showed, the courage, humility, and continued generosity.” Evidently, Doug Birdsall has a lot to learn about “people.”

Failure of the Usual Suspects

Despite the wave of legislation and compliance offices that sprung up in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis 14 years ago, then, as now, the trouble was a series of increasingly irresponsible and complex loans that enabled transactions with little visibility. As long as housing prices kept rising, lenders ignored the growing risks. Only when homeowners stopped paying did reality bite: The banks had financed so much borrowing that the fallout uncontainable.

While the Archegos collapse didn’t trigger a market meltdown, it is the same old Wall Street story. Risk met greed, and the latter won out – facilitated by overwhelmed regulators sleeping at the switch and lender-banks and others who greased Bill Hwang’s unrestrained hubris as he lined their pockets.

Demanding visibility to his operation, limiting the leverage extended, or increasing his margin requirements would have all prevented or, in the least, significantly mitigated Bill Hwang’s catastrophic crusade. European laws require the party bearing the economic risk of an investment to disclose its interest. After two decades of fraud and scandal, what is so difficult for the U.S. government to understand such a basic legislative need?

We all know it. Congress even heard it in its January hearings following the GameStop Corp. debacle. Not only is there not enough transparency in the stock market, but the instruments and behind-the-scenes manipulations are only comprehendible by manipulators. Wall Street is not just too big to fail. It’s getting too complex to save.

As he repeatedly put fire to dynamite, had Bill Hwang not been able to be “the greatest trader you’d never heard of,” this and smaller debacles routinely covered up, and even larger ones to come in the future would not be possible.