In this, the last in our Black History Month “Black Russians” series, we actually take a look at contemporary black Russians (including black Soviets, whose birth and nationalities are issued of a diaspora African fathers and Russian or formerly Soviet mothers), of which the Metis Foundation estimated that they were about 50,000 in 2009.

Pushkin was a black Russian. This has been well-publicized. The extent of an American’s conception of people of African descent in Russia and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union is indeed Alexander Pushkin. In the third installment of the black Russian series, we explained Pushkin’s ancestry to the great 18th-century Russian general and nobleman, Abram Petrovich Gannibal – a kidnapped boy from Cameroon who fell under the tutelage of, and was educated by, Czar Peter the Great to become a renowned professor of mathematics and engineering in all of Russia.

But today, the “negres” or “negrys” of the East – are largely invisible to us in the West when we speak of the African diaspora. In this, the last in our Black History Month “Black Russians” series, we look at the black Soviets of today (or black Russians as we will call them out of ignorance to local, national identities).

With the tradition of the thriving black Russian community at the Imperial Court coming to an end in the early 20th-century, as the small black Russian community became more or less mixed, it became more invisible inside Russia until a new infusion under the Iron Curtain.

Contemporary black Russians (former Soviets) live in and outside eastern-bloc countries, are of diverse paternal backgrounds, yet with the common bond via a Russian or Soviet-era mother. Most are of African, American, or Caribbean fathers who left Russia for various reasons – mostly upon expiration of student visas, for expulsion for marching or protesting against racism, and voluntary departure to take the “revolution” to different parts of the world.

Since time immemorial, migration, occupation, and foreign exchanges have produced people of mixed race, cultures and tradition. Among famous examples of antiquity is the Deuteronomic writers wo had emerged from Babylonian captivity (circa 538 BCE) with a revised (Yahwist-Elohist-Deuteronomic-Priestly) version of the Torah. In modern times, the United States has been the face of a diversified the nation by immigration.

Since time immemorial, migration, occupation, and foreign exchanges have produced mixed races, cultures, and traditions. Among famous examples from antiquity are the Deuteronomic writers who had emerged from Babylonian captivity (circa 538 BCE) with a revised (Yahwist-Elohist-Deuteronomic-Priestly) version of the Torah. Roman soldiers who fanned out across Europe centuries later left wide footprints in the form of offspring that changed local racial makeup.

In modern times, the United States has been the face of a nation diversified by immigration. But not all emigrate to America for a new life. Many come as students who return to their respective countries, leaving behind pivotal traces, as in the case of one Mr. Barack Obama Sr. In the same way, the Soviet Union was a destination for students from far apart in the developed and developing world.

Invariably, like the presence of the Roman soldiers or even that of the Americans who fought in the 1960s-era Vietnam War, many black students who came to study in the Soviet Union left wide footprints in the form of offspring – a mixed race of black Russians, even in remote parts of the former Soviet Empire.

I once met a Catalan national who was born in Bulgaria to Mexican and Bulgarian parents. On both sides, her parents were socialist revolutionaries. Her ancestor, three generations removed, had fled Spain for Mexico. Two generations of her family were born elsewhere in Latin America, including a parent who later fled to the Soviet Union and was placed in Bulgaria. History then dictated not only the unity of two individuals of immensely prominent lineage in their respective countries’ political and revolutionary hierarchy, but also my friend’s birth into what was then the Soviet Union’s system of accepting socialist and communist adherents from the far-flung parts of the world for studying, training, and indoctrination.

The Emergence of New Black Russians

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International (1919–1943), was an international organization controlled by the Soviet Union that advocated world communism and the “struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie.” A small coterie of African-American intellectuals and families came to the Soviet Union under the auspices of the Comintern and stayed. Some of their descendants would constitute the first new wave of black Russians in the mid-20th-century.

With the wave of African independence from European colonialism, the Soviet Union offered scholarships to an estimated 400,000 young Africans to study throughout the former Union between the late 1950s and 1990s. The 6th World Festival of Youth and Students, held in Moscow in 1957, heralded the first significant arrival of African students, many of whom attended the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. Black students from the Caribbean and Latin America had also arrived.

Festival Children

As the black students intermixed with local women throughout the Union, a new generation of “Festival Children” emerged – mixed-race black Russians and Soviets – so named because of the timing and circumstances of their births, their mixed and very different look, and the general lack of father figure, who had returned to their home countries. In this sense, their circumstances bore similarities to the Afro-Vietnamese offspring of black soldiers and local Vietnamese women during the Vietnam War.

An Invisible Generation Searching for its Place

Think of a tree growing, where the roots on one side are poisoned. Its physical ability to grow, thrive, defend itself from insects & pests, and bloom are seriously impaired. With a human being, maturing to full social capacity is much the same. The neural firings and growth that form the basis of the human experience are short-circuited – replaced instead by imagination. A salient fact of life is that you cannot recall what you have not experienced – physically or socially.

This is the case of a generation of contemporary black Russians (Soviets), most of whom self-describe as Afro-Russians and have grown up without much contact with the black parent other black people. They came of age without the shared cultural experience and identity building blocks as blacks in the Caribbean, Latin America, the United States, Britain, Canada, France, and so on – each with differing levels of black identity or association to a common African ancestry.

In the mid-90s, I had two experiences in Europe that highlighted the detriment of cultural alienation – “black without “blackness.” The first was the case of a dark-skinned black friend who went through an almost comical early-thirties transformation. His mother was a light-skinned Caribbean woman, and his father, an African man who had left his mother before my friend was born, so he never knew his father. His mother then married a white European man with two white daughters from a previous marriage. This stepdad then adopted my friend in infancy and raised him as his own.

By all counts, my friend had a beautiful “white” upbringing with loving parents and two loving white sisters. He was raised in a “very white” village (no blacks) in the south of France with the usual “only black” experience in almost everything.

He then took a trip to Africa for a month and returned wearing dashikis and beating drums on the streets of Paris (he was already a musician). He was a different person, determined to “out-black” the rest of us – extreme in attitude and perceptions of what a black person “should be.” Having suffered identity-alienation his entire life, he now objectified and simplified the realities and humanity of racial identity on the authoritarian spectrum. In no time, I had to face reality – I had lost a friend.

In another case, I was hanging with a friend in a bar in a major European capital when a beautiful mixed-race black woman approached. “Hey there, my beautiful sister,” I said, casually flirting with her. I had no belief that she would have responded and was very surprised when she did. She wasn’t flattered because I called her beautiful but was rather mesmerized that I had called her “sister” – commonplace in anywhere America or Britain. We then talked over drinks for more than an hour, and she told me of her elation the first time she had visited London and someone had called her “sister.”

She had also just returned from New York – her first visit to the United States and was brimming with the excitement of how welcomed she felt in New York, visiting and meeting people in Harlem and elsewhere in the city. For the first time, she felt that she “belonged.” I felt the genuine sadness of her upbringing and reflected on the little things we take for granted in America, the Caribbean, Latin America, and elsewhere in Europe. Through slavery, segregation, and discrimination, our racial identities were solidified (even if alienated from Africa).

So imagine the lifetime of difficulties that black Russian (Afro-Russians) have endured. As mentioned above, the homogeneous eastern bloc is not known for its intolerance of “the other” – particularly black people. We still see evidence of this with each playing of a EUFA Cup football match with black players from western Europe. The history of unfamiliarity and discomfort with blacks is always on display with the taunting and racist attacks on black players from Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and so forth. So, the common struggle for black Russians is unimaginable.

Testimonies

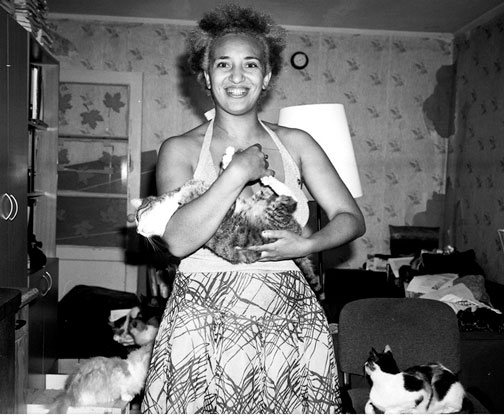

Liz Johnson-Artur

Photographer Liz Johnson-Artur and many contemporary black Russians from throughout the other former Soviet states are examples of this phenomenon. She is the daughter of a Bulgarian mother and a Ghanaian father who came to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. After four years studying biochemistry in Bulgaria, the country expelled all Ghanaian students following a confrontation between black students and the police. By then, her father had already met her mother, who gave birth to their daughter in 1964, a few months after his departure. Her father was unable to return to Bulgaria and now lives in Ghana.

“The amount we know about our African heritage varies from individual to individual,” she says. “Those who grew up and live in Russia still have to justify on a daily basis the fact that they are Russians too. When people ask me about my background I usually start by explaining how my mum is Russian, my dad is Ghanaian, and that I was born in Bulgaria. It often becomes a long explanation. Most black Russians that I met in Moscow and St Petersburg had also grown up without their fathers. Some had been fostered or grown up in children’s homes and had never met their mothers. But we all agreed that we felt Russian as well as African.”

Ivan

Ivan is a black Russian of a Russian mother and a Malian father. “I lived with my mum, but we didn’t get on. She didn’t understand me,” he said. “I used to run away a lot, but they always caught me and brought me back to her. When she couldn’t take it anymore, I moved in with my grandmother, but it wasn’t any better. A lot of what I learned, I learned on the streets. Kids use to try to pick fights with me, and I fought back. I left the army with a drug habit, and when I got back to Moscow, I lived on the street. It was tough.”

Despite the obstacles, this black Russian kicked his drug habit and discovered beatboxing, which gained him his own show on MTV Russia.

Marie-Therese

Marie-Therese is making the best of being a black Russian through discovering her Russian ancestry in late-stage rather than living it in childhood – at the sacrifice of her racial identity. “I was born in St Petersburg. Both my parents worked for the UN. My mum is Russian, and my dad’s family is from Guadeloupe and Brittany. My mum’s family left Russia after the revolution. Because of my parents’ work, I lived for ten years in Africa – Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, Ethiopia. I moved back to France for my baccalaureate, and after I finished my law degree, I took part in an exchange program. I had a choice: Bangladesh or Russia. I chose Russia and came to St Petersburg in 1995.

Gera

Like my Catalan friend, Gera owes his Russian birth and life as a black Russian to a revolutionary Cuban father and local Russian mother. Life, though, has put him through the wringer as a black Russian. Yet he seems to have eked out a black identity, of which he remains proud. By the looks of it, Gera is typical of a black musician you might meet in Rio de Janeiro, Havana, Kingston, London, Paris. But he sums up the black Russian experience in six words.

“I was born in Moscow in 1961,” he says. “My dad was a Cuban revolutionary who came to Moscow to study philosophy. He fought with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in Cuba. When I turned one, he went to fight with Che in Bolivia. I only saw him once. My childhood was not easy, but I have always been proud of being black. Growing up, I got a lot of attention, and a lot of it was not good. Russia is quite a chauvinistic country. They don’t like black people here.”

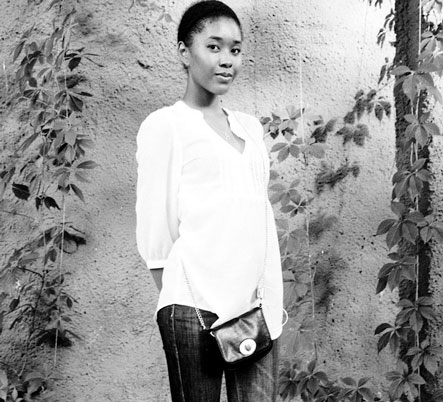

Amina

For black Russians Amina and Vlada, life often resembles a freak show – if venture outside of cosmopolitan Moscow. It’s a mix of unfamiliarity and provincial dispositions that makes them Russia’s modern-day versions of the “Hottentot Venus” meeting eastern Kentucky. Their safety is endangered, and they become strange objects with features to be viewed and touched.

“I was born in Moscow,” says Amina. “My mum is from Russia, but she is Asian – from the Tuva Republic. My dad is from Nigeria. They met at university in Moscow. Just before I turned five, my dad left. For some reason, he never returned. When I finish my studies, I would like to leave Moscow. In the center of Moscow, I feel fine too. But I don’t really go to the outskirts of the city: it’s a very different atmosphere. I am used to being looked at, but outside the city center, I don’t really feel safe.”

Vlada

“I have lived in Moscow for seven years,” she said. “Most of the time, I feel fine here, but I would like to live in a different place. I have traveled to Brazil and Spain. People are different there, more friendly and open. Moscow is a beautiful city, but people here can be quite hard and very nosy. Strangers trying to touch my hair is something I really don’t like.”

Peter

For Elena and her teenage son Peter, life is anything but normal. His father is Nigerian. As a baby, Elena says people used to try to look in the carriage to see the skin color of the black Russian baby. Friends and neighbors shunned her. Parents complained to the nursery about taking on a black child, and at school, the children would say things like, “If you touch him, your hands will get dirty…”

The Immigrant – George

George is a black man who came to Russia from Cameroon as a medical student and stayed. Around 2004, skinhead violent racist attacks were common in St Petersburg. After they killed an African student, George was part of organizing a big demonstration in the city, where he also spoke at the rally that followed. This brought him to the attention of the FSB – the Russian security services, who detained and questioned him for two days.

He is the father of black Russian children with local women. Looking for work on arrival in St Petersburg rekindled to his passion for martial arts, so he started giving martial arts lessons. “Russia was good to me,” George says. “It gave me the opportunity to open my own martial arts studio. I could have never done this in Cameroon.”

His attempts to join the service since then have been denied, despite passing all of the tests. “It takes time for attitudes to change,” George says. “I also tried to join the FSB. I passed all the tests but they wouldn’t take me.” Poor George now works for them voluntarily under the fleeting delusion that they might one day hire him.

End

Having spent her childhood in Bulgaria and then Germany, Liz Johnson Artur has been based in Britain since 1990. She met her father for the first time, as a 46-year-old woman, in 2010. This inspired her to start documenting the stories of other black Russians of African and Caribbean origins. She hopes her project will encourage others to connect and bring visibility to this almost invisible generation of black Soviets who have grown up knowing only Russia, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and other places as home.

If you like this story, please like and share

External sources: Testimonies from The Calvert Journal

1 comment

Excellent read on Black Russians in particular the impact of growing up not knowing your true identity. Well researched and well written.