The B.1.1.7. coronavirus mutation is the variant recently discovered in the U.K. – the country with some of the best genome sequencing capabilities in the world. It vigilantly searches for virus mutations and tracks them. So, while other countries, including the U.S., have not been searching for or tracking mutations as closely, they might have missed detecting the B.1.1.7 mutation and others happening locally as well. Since Britain’s revelation this past weekend, researchers have identified the mutation’s variant in Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Italy, Spain, and Australia.

Viruses always mutate. It is their nature – in their quest to perfect themselves for more efficient and effective host domination. SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, is no different. So this coronavirus mutation is unsurprising to the experts. It has been mutating at a rate of about one or two mutations a month, which is not surprising. As global scientists rush to figure out the new mutation emerging in the U.K. and the level of threat it poses, the infinite words of George W. Bush’s former defense minister, Don Rumsfeld (the Iraq Guy), come to mind. “There are known knowns and known unknowns.” Life is a combination of facts and speculations.

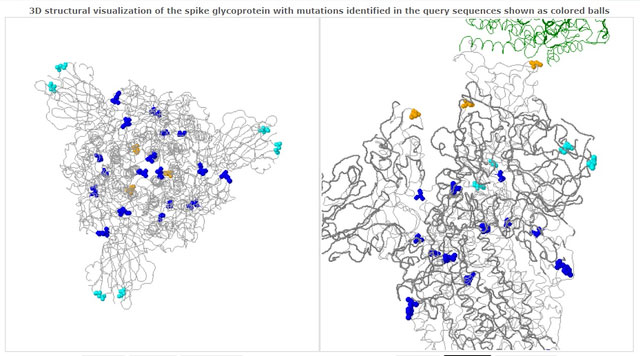

The Covid-19 Genomics U.K. Consortium, which brings together universities, medical research institutes, and public health agencies, has, since the beginning of the pandemic, mapped the genetic makeup of almost 150,000 virus samples taken from infected individuals. They upload their findings to a global initiative called Gisaid – an extensive database that collects similar data from scientists across the world. A scientific paper written by researchers involved in the consortium and published online outlines the B.1.1.7. coronavirus mutation’s features.

B.1.1.7. “Known Knowns” and “Known Unknowns”

At this point, scientists do not know everything about this newly discovered coronavirus mutation because it has just emerged. So far, people infected by the B.1.1.7 strain do not seem to be getting sicker. “There is absolutely no evidence that this [variant of the] virus is more deadly,” says biochemist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Jeremy Luban. “There’s nothing at all to suggest that, and I don’t think anyone that I know is worried about that possibility.”

Again, we are in its early stage, so we can be sure of very little. We must be mindful of the tightrope that public health officials are walking – balancing the need to dispense caution without creating public panic. But we must also keep in mind the number of public blunders that have led to massive propagation and death – from failure to mandate early mask-wearing to late discovery and acceptance of the virus’ aerosol transmission.

B.1.1.7. Mutation

British scientists first detected this new coronavirus mutation – B.1.1.7 – in late September 2020. Since then, it has rapidly taken over parts of England – pushing out other forms of the virus to become the dominant form. The mutation now accounts for more than 60% of the cases in London and the greater South East, and scientists say this mutation is more contagious than previous versions of the virus. “This rapid rise suggests B.1.1.7 is more transmissible than other forms of the virus,” said Dr. Luban. “There’s no hard evidence, but it seems most likely. So if a person sneezes on a bus, the new variant is more likely to infect other people than the previous form of the virus.”

In November, the mutated B.1.1.7. made up around a quarter of London’s cases; this reached nearly two-thirds of cases in mid-December. Like most viral mutations, it is rapidly replacing other versions of the virus to become the dominant strain. It has acquired mutations much quicker than scientists expected – with 17 relevant genetic code modifications (23 if other we count minor ones). Eight of those mutations occur in a critical part of the virus, called the spike protein, which reaches out and binds itself to human cells during the initial infection stages.

In particular, scientists have identified one mutation – N510Y – that makes the virus bind more tightly to human cells. This protein is a perfection in the virus’s ability to bind (infect) to human cells. Scientists believe that the N510Y mutation appeared independently.

South African Variant – 501.V2

In South Africa, another coronavirus mutation is also underway – 501.V2 variant. It shows some similarities to the one identified in the U.K, but scientists now believe it mutated independently in South Africa. 501.V2 mutation is now the dominant strain driving the second wave of infections across the country with a higher transmission rate and high prevalence in the young. There is now speculation that this mutated strain might elude antibodies of the previously infected, which would also portend poorly for vaccines. According to Salim Abdool Karim, an infectious diseases epidemiologist and Director of the Centre for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa, “We are finding between 80% and 90% of the virus is this 501.V2 mutant.”

D614G & 69-70del

Another mutation – D614G – makes the virus more transmissible. B.1.1.7 also contains a small deletion in the virus’s genetic code – 69-70del – and that deletion helps the new variant evade the body’s immune system in some people. This is cause for even greater concern. These mutations, combined with the fact that B.1.1.7 acquired many changes simultaneously, suggest this new variant didn’t arise by chance but that the modifications give it an advantage – a normal biological evolution. They are helping the virus adapt to more effective host domination in order to thrive.

Impact on Testing

As for the coronavirus mutation’s impact on current testing capabilities, associate professor infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco, Babak Javid, told The Wall Street Journal that the coronavirus mutation has helped researchers track the variant’s spread in Britain. The standard polymerase chain reaction, or PCR tests for the coronavirus home in on three segments of the virus genome. But one of those signals fails with the new variant. That two-thirds result has become a telltale sign of this specific variant in lab results.

Impact on Vaccine / “Vaccine Escape”

The frightening possibility that the virus could mutate to dodge the vaccine’s full effect, vaccine escape, also exists. This would profoundly affect the mega-vaccine rollout now underway in the U.S., U.K., and beyond. Vaccines propel our immune systems to make many antibodies against big chunks of a virus, not just one small section that could change when the virus mutates.

So even if the variant contains 17 mutations, some antibodies targeting the vaccine will likely still bind and neutralize the virus. But again, we cannot be sure. Johns Hopkins University microbiologist Andrew Pekosz advice is, “So if you’re in line for the COVID-19 vaccine, stay in line. Don’t give up your spot. Take it. You know, everything is still looking good from the vaccine standpoint.”

So, scientists remain optimistic about these coronavirus mutations. But regardless of their protestations or that of politicians and public health professionals, science does not yet know for sure if the vaccines will be effective with B.1.1.7. or 501.V2 as they are with previous forms of the virus. Laboratory testing of the new variant and intensive vaccination efforts in areas of known propagation, such as London and the greater South East, U.K., must first be done.

Scientists believe that as the coronavirus is already spreading rapidly worldwide, a small increase through mutation might not make a big difference. It depends on how much better these new coronavirus mutations spread, which is the real question. In the mind of the natural viral programmer, Why increase its efficiency without increasing its effectiveness to do battle? Additionally, the new coronavirus mutation’s increased transmissibility inevitably translates into higher death rates for CoV-2 and non-Cov-2 patients as hospital and care facilities will be inundated.

In the end, the tried and worn common sense that has been wanting in the coronavirus-era remains the same. Virus expert Pei-Yong Shi at the University of Texas Medical Branch reminds us of as much:

In the end, how quickly the virus spreads depend on many factors, including people’s behavior in a community. That is, whether they wear masks, physically distance and avoid big gatherings. Those factors could be more important than whether B.1.1.7 arrives in a community. With all these human interventions, it’s hard to predict the course of the pandemic.

Pei-Yong Shi, University of Texas Medical Branch

If you like this story, please subscribe and share, if possible