Frederick Thomas died in a Turkish debtor’s prison in 1928 at age 56. But at the time of his death, this unique African American turned “black Russian” had built and lost an empire to a revolution in Russia and xenophobia in the new Turkish Republic.

As mentioned in our first installment of Black History Month’s “Black Russian” series, many books have since been dedicated to the path from “Harlem to Paris” and the usual suspects – Josephine Baker, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Sydney Bechet, Augusta Savage, Bricktop, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, Richard Wright, Meta Vaux Fuller, Jimmy Baldwin, and many others who found fame in Paris. But history, in particular, black history has either underrepresented or mostly ignored other great men like James “Wink” Winkfield and Frederick Bruce Thomas (Fyodor Fyodorovich Thomas). Both had realized extraordinary accomplishments in Russia and elsewhere in Europe, with Thomas leaving a considerable legacy in Turkey as well.

On July 8, 1928, The New York Times gleefully reported the following byline: “American Negro Who Made and Lost Fortunes Died Penniless and in Debt.” It reported the death of African American Frederick Thomas in a Turkish debtors’ prison. It was the unceremonious final contact with the ground by a black Icarus who had flown way too close to the sun.

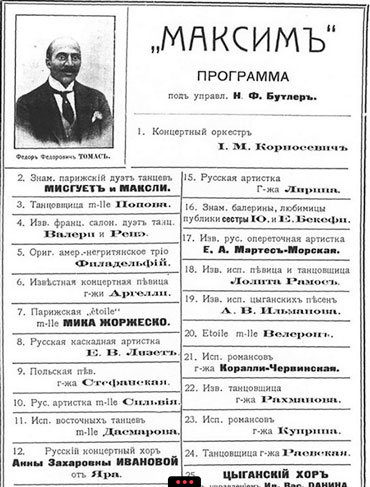

According to the Times obituary, “The American negro, Frederick Thomas… was the Sultan of Jazz in the new [Turkish] republic… He founded Maxim’s. This cabaret soon became the leading resort in the nightlife of the city. For talent, he drew upon the Russian genius in matters of cuisine, decoration, and amusement,” the article mentioned. “…He died yesterday, leaving a Russian wife and two children. It is said that he was a sailor who left his ship at some Russian port in pre-revolutionary days, though none knows how he earned a livelihood in Russia.”

Mississippi’s Frederick Thomas To the Land of The Czars

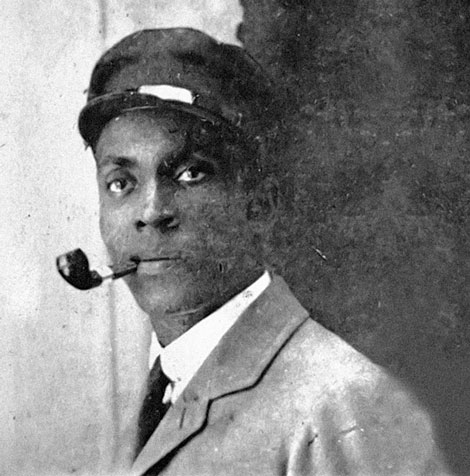

Frederick Bruce Thomas, born in 1872 in Mississippi to freed slaves. After his father’s brutal death, the teenage Thomas fled the South for Chicago and then to New York, where he worked as a valet and trained as a singer. From there, he then set sail for Europe. In the late 1890s, after much traveling and learning to master French, he became a master waiter and valet, working for a Russian nobleman in Monte Carlo. Thomas’ developed an interest in the Land of the Czars, and he arrived in Russia in 1899.

This was ten years before James Winkfield would ride for the Czar and more than two decades before Josephine Baker and Sydney Bechet would disembark in Paris. For the first years, Thomas worked in restaurants and hotels across the country but later, he eventually settled in Moscow.

In his native of Mississippi, Frederick Thomas had seen the very worst of Jim Crow and black oppression. But in Czarist Russia, he had become rich and successful as the owner of Moscow’s most popular nightclubs and later, a leading figure in the Russian emigre community in Constantinople during a time when blacks were suffering oppression and exclusion in the United States.

Described as handsome, charming, charismatic, and debonair, Thomas was very popular with women. His skin color seemed to have worked in his favor in Russia – rendering him somewhat exotic to the Muscovites and endearing to many aristocrats and powerful businesspeople in the city, many of whom he soon befriended, many of whom spring boarded him into social access that brought him immense financial success.

The life of Mr. Thomas in Russia was an upward spiral of success, fame, and fortune, as he became one of the most innovative, influential, and powerful theater impresarios in Moscow, which was then Russia’s second most important city.

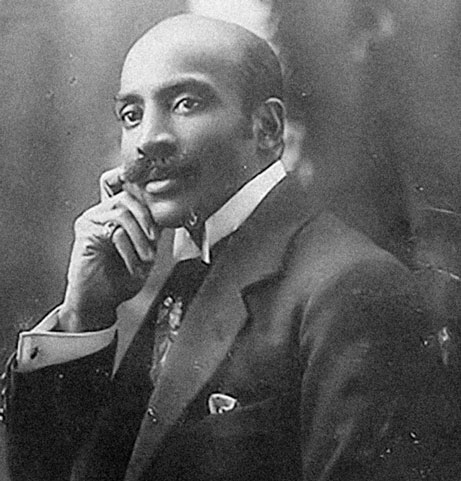

Professor Vladimir Alexandrov, Author of The Book “The Black Russian”

In The Black Russian, Yale University’s Professor Vladimir Alexandrov gives us an insight into Frederick Bruce Thomas’s life (1872-1928) in Imperial Russia and beyond. In an email interview with the website Russia Beyond (source), Professor Alexandrov said, “The life of Mr. Thomas in Russia was an upward spiral of success, fame, and fortune, as he became one of the most innovative, influential, and powerful theater impresarios in Moscow, which was then Russia’s second most important city.”

Frederick Thomas Becomes “Fyodor Fyodorovich”

In 1903, Thomas worked as maître d’hôtel at the popular cabaret Aquarium. By 1908, he was working as maître d’hôtel at Yar, a popular club frequented by the Russian elite and famous figures such as Rasputin, the charismatic monk who had leveraged enormous control over the Imperial family in St. Petersburg. After a renovation period, Yar reopened in December 1909, by which time Frederick Thomas had become an important figure there.

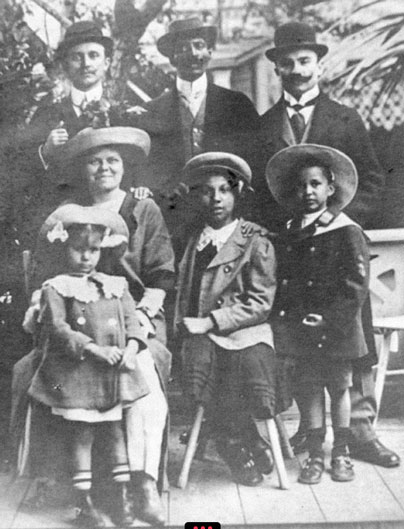

Unlike James Winkfield, Frederick Thomas integrated into Russia, became a Russian citizen, and left a substantial footprint in the form of five black Russians – his offspring who likely carried his DNA into future generations. In 1901, Thomas married Hedwig Hahn, a Prussian Protestant woman, a union that produced three children. She died of pneumonia in January 1910, at which time a Baltic German nanny from Riga, 28-year-old Valentina Hoffman, assumed care for Thomas’ children. In 1913, Thomas married Hoffman and moved his family into an upscale apartment at Malaya Bronnaya, 32, near Patriarch Pond.

In November 1911, Aquarium reopened with new owners. Frederick Thomas was no longer an employee but instead one of the new owners. Under his management, Aquarium blew the lid off the only other serious cabaret competitor in Moscow – Hermitage Garden. By summer 1912, Thomas was a rich man. Aquarium’s first season had had a profit of 150,000 rubles — (about $75,000 or equivalent to $2 million today), which put him among the top theatrical entrepreneurs in the Russian Empire.

In fall 1912, Thomas traveled to other Russian cities looking for performance acts for the 1913 summer season. He then took over a failed club, Chanticleer, at Bolshaya Dmitrovka, 7, renamed it Maxim, and opened it on November 8, 1912. At Chanticleer, the entertainment started at 11 p.m. and continued into the morning. His cabarets were racy and sexual venues that became a major hit.

However, things did not flow as smoothly as expected, and Frederick Thomas’ plans for Maxim’s soon ran into a serious stumbling block – the church. Three Russian Orthodox churches were within proximity, and the Church had restrictions on theaters and cabarets. As a measure of his connection and standing in the Moscow establishment, Thomas soon got the necessary city permission to open his club.

The lavish Maxim’s became a huge success among Moscow’s elite, along with Frederick Thomas’ fame and fortune. Within a decade, he became Moscow’s entertainment king. Aiming to finance the opening of new theaters in Moscow and other Russian Empire cities, Thomas and his partners launched the First Russian Theatrical Stock Company in January 1914, which had 650,000 rubles in market capitalization (about $10 million today) in no time. Along the way, he also took on a German mistress with whom he had other children.

It is no coincidence that Thomas had chosen to call his Moscow club Maxim. Paris’ famed Maxim was opened as a small bistro at 3 rue Royale two decades prior, in 1893 – by a former waiter, Maxime Gaillard. Frederick Thomas had likely visited Maxims during his time in France and knew its history. In Maxime Gaillard, Thomas, himself a former waiter, had found a model.

However, the approach of World War I ended those plans, as Russia went on a war footing. But even then, Thomas’ clubs continued to thrive and as popular destinations, adding to his fortune. With his thriving business interests and family, Frederick Thomas signaled confidence in his new homeland by taking Russian citizenship in 1915. His confidence in his and the country’s future was also on display with his real estate investments in February 1917. Along with a villa outside of Odessa, he bought six adjoining buildings in downtown Moscow with 38 rental units.

Frederick Thomas Escapes A Revolution

Although he planned to stay in Russia, like James Winkfield, the Revolution forced Frederick Thomas to rethink. As Russia started to splinter, so did Thomas’ life. The Bolshevik’s October 1917 power seizure ushered in a new and radical social and political order. In the first half of 1918, they nationalized all private property, destroying everything that Thomas had built.

Compounding his sense of loss and humiliation, Frederick Thomas then caught his wife in bed with a Bolshevik commissar – a dangerous liaison that almost ended Thomas’ life. It is said that she goaded her Bolshevik lover to kill Thomas, not on racial grounds but as a “class enemy.” But her lover couldn’t pull the trigger.

For obvious reasons, Thomas became an easy target for secret police surveillance. It was time for him to flee, and in August 1918, he left Moscow by train, making his way to his villa outside Odessa, at that time occupied by the Imperial German army. His mistress and children were waiting for him there. After nine months at the Odessa villa, he left Russia by boat with his mistress and their children to a new life in Constantinople (then Istanbul).

The Sultan of Jazz – Frederick Thomas in Constantinopole

The Turkish Gazinos are nightclubs – cabarets venues for food, drinks, and musical entertainment, whose popularity dates back to the beginning of the 20th century and to its patron, the so-called Sultan of Jazz – African American Frederick Bruce Thomas. In Constantinople, Frederick Thomas became rich again, doing what he knew best. He brought jazz to Turkey, soon becoming known as the Sultan of Jazz with the opening of a series of celebrated gazinos, which, at the time, was a new phenomenon for the Turks and their multi-cultural city.

Thomas opened Stella – the city’s first entertainment venue – in Şişli. A few years later, he moved to a new site in Taksim. In 1921, he opened Maksim’s (another Maxim’s) adjacent to the Cinemajik theatre. It had Russian décor that served Russian food and catered to both locals and the Russian emigre community. Maksim’s quickly became a hit with the upscale locals, visiting jazz bands, and tourists – the place where people came to show off their “Foxtrot,” “Charleston,” and “Black Bottom” dance moves.

However, unlike the cosmopolitan Moscow, the xenophobia of the new Turkish Republic played against Frederick Thomas. Istanbul was not as oblivious to his skin color as Moscow. Additionally, local Istanbul perceived Thomas as extravagant. He also lacked the connections he had acquired in Moscow, so caught up in the intricacies of patriotic and xenophobic fervor in the newly formed Turkish Republic, Thomas ran into difficulties.

He sought help from diplomats in the American Consulate General in Constantinople. But the racism there was even worse. The Consulate General refused to even recognize Thomas as an American or to give him any legal protection. Abandoned by the United States, he was isolated and soon fell on hard times. He lost his businesses and ended up in a debtor’s prison, where he died in Constantinople in 1928, aged 56.

Frederick Thomas’ Legacy

Today, his legacy remains in modern-day Turkey’s gazinos – the high-end cabaret and prestigious music haunts of upscale and local celebrities. Since the 1950s, many of Turkey’s most famous celebrities have graced the stages of venues such as Büyük Maksim (Grand Maksim) and others or as patrons. That which Frederick Bruce Thomas had brought to Istanbul remains a staple entertainment form in the city a hundred years later.

Thomas’ New York Times obituary gleefully described him disparagingly as “extravagant and reckless.” Yet Russian emigres and tourists in Istanbul had remembered him fondly. The New York Times could not bring itself to recognize Thomas’ talents and skills, like learning a foreign language, adopting the high etiquette of service to Russian nobility in Czarist times before branching out into his own affairs.

The New York Times was deigned to acknowledge the black Thomas as a celebrated businessman in two foreign countries, and it gave the impression that he had reached Moscow by absconding a ship on which he worked. More importantly, though, was the obvious: How many other black men could have even earned a mention in a 1928 New York Times edition unless they had truly racked up extraordinary accomplishments?

As for Russia under the Bolshevik regime, Moscow photoshopped Frederick Bruce Thomas out of its historical album. Successive communist regimes then made it a ban because he was a capitalist. The new Turkish Republic had no space for historical visibility for non-Turkish nationals. As a result, Frederick Bruce Thomas’ legacy and memory were largely discarded as a historical data point until Professor Alexandrov researched his life and published “The Black Russian,” which spotlighted this extraordinary chapter in America, Russian, and Turkish history in the nexus of one man – African American Frederick Bruce Thomas, the son of freed slaves in the Mississippi Delta who, before disappointment, had made it big in the latter two countries.

If you like this story, please subscribe and share, if possible

External Sources:

Vladimir Alexandrov’s “The Black Russian“

Russia Beyond – “How the son of freed American slaves found fortune and glory in Imperial Russia“

Oxford University Press blog