James Winkfield will hardly figure among the coterie of online resources dedicated to facts, fiction, and outright propaganda of African and African-American achievements in foreign lands. Yet, along with Frederick Thomas – later Fyodor Fyodorovich Thomas, no two African Americans are more accomplished yet under-recognized for their exploits in foreign lands. This is largely due to the bias in research to those who made their names in Paris, which had become a category destination for African Americans since the “Freedmen of Color” somewhere around the 1840s.

Many books have since been dedicated to the path from “Harlem to Paris” and the usual suspects – Josephine Baker, Henry Ossawa Tanner, Sydney Bechet, Augusta Savage, Bricktop, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, Richard Wright, Meta Vaux Fuller, Jimmy Baldwin, and many others who found their mojo in Paris. But along with fighter pilot Eugene Bullard (himself of extraordinary French accomplishments), and others like Frederick Bruce Thomas, history, in particular, black history, has either underrepresented or mostly ignored these other these men who had realized extraordinary accomplishments in Russia and elsewhere in Europe, leaving considerable legacies in Rusia, France, and even in Turkey as well.

In honor of Black History Month, this is the first of three installation in our Black Russian series.

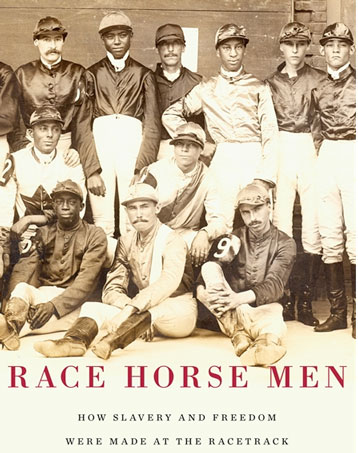

James Winkfield – An African-American Jockey

African-American jockeys developed America’s original sport, horse-racing (way before baseball took the mantle). Andrew Jackson so loved the sport that he took along his horses and his black jockeys with him to the White House when he became President. In the early days, some of the first successful jockeys in the were black. It was the only sport in which African-Americans were able to compete with whites.

For example, in 1875’s inaugural Kentucky Derby, 13 out of the 15 jockeys were black. Among the first 28 winners of the Derby, 15 were black – and African-American dominance of the sport that would last through 1921. Since then, they were largely written out of its history.

Among the great names are Monkey Smith, Oliver Lewis, William Walker, Isaac Murphy (America’s first true black celebrity), Alonzo “Lonnie” Clayton, James “Soup” Perkins, Willie Simms, and the legendary James “Wink” Winkfield – two-time Kentucky Derby winner in 1901 and 1902 and the last African American to win the race. The era of greatness for African American jockeys at the Derby had ended.

After living under intense violence and constant death threats from the Ku Klux Klan, James Winkfield fled America in 1904 for Czarist Russia during the time of Emperor Nicholas II, where Winkfield’s riding skills gained him fame, fortune, and appreciation beyond his wildest dreams and where he would bear witness to the waning days of the Romanov dynasty.

With the approaching Bolsheviks in 1917, James Winkfield escaped Odessa, leading a colony of horses, jockeys, women, and children to Romania, from where he, his men, and the horses would reach Warsaw, Poland, by traversing the Transylvanian Alps, crossing Hungary, Czechoslovakia, in a two-month journey to finally meet in Warsaw Poland. In Warsaw, he saw stardom that would later be repeated in Austria and Germany, with an eventual life in Paris at its heydays, until the Nazis entered France in 1940 and subsequently seized his farm, forcing him to flee back to the United States. In 1953, he was back in France, where he opened a training school for jockeys.

James Winkfield – To Russia With Love

A stream of American jockeys, white and black, had been leaving America for Europe in those days, mainly due to their desires for prolonged careers in face weight restriction in America, which shortened many careers and racist hostilities facing the black jockeys. Willie Simms had opened the door in the mid-1890s, and though he did not stay in England, other Americans such as Tod Sloan had found great success in Europe. In the case of Sloan (who was white), he had taken the same American Seat perfected by slave jockeys (the ‘negro couch’) to become a great star and famous playboy in England.

A visiting Russian turf official remarked in 1904 that, “In all European countries, the scale of weights is higher than here, and this is especially true in Russia.” With that, James Winkfield, who never had a weight problem but facing intense racial violence on and off the tracks, said, “So that winter, when I got a chance to go to Russia, I went…”

Before getting permission to go to Europe, jockeys needed to secure a contract from the host country. Lexington trainer Jack Keene was training horses in Poland and Russia for various stables but had run into some difficulties. Keene was an acquaintance of Winkfield’s, and the timing of Keene’s difficulties abroad worked to the advantage of Winkfield, who was looking for a way to leave America.

A doping investigation in Moscow (again, another sporting phenomenon with origins in horseracing) involving Keene and his best jockey, American Carroll Mitchell, resulted in both their suspension from racing. Keene asked Winkfield to travel to Russia and take care of the riding and training operations while he – Keene, had to lay low.

Winkfield’s first stop was in Poland, where Keene’s horses were being trained, and he went straight into doing what he knew best. “They gave me a book, so I could learn Polish… and I rode two winners on opening day,” Winkfield later said.

As it would turn out, Keene, who had sent Winkfield to deal with his business until the heat from the doping scandal was off him, did not show up for many years. Wink then started to work with and ride for Armenian oil tycoon Michael Lazareff, who owned most of the horses in Keene’s stable, as the leading stable owner in Poland as well. Winkfield worked for Lazareff’s northeast circuit – from Warsaw to Moscow to St Petersburg and then back to Moscow.

I went down to Moscow and won the Emperor’s Purse that year, worth about 50,000 rubles… We really cleaned up.

James Winkfield

According to author Edward Hotaling (who wrote extensively on America’s black jockeys), Russian reports indicated that Lazareff made about 300,000 rubles in winnings that year – the bulk of which was won by Winkfield. As a result, said a Russian correspondent, “Jimmy Winkfield has made many friends among the Russian sporting fraternity, and the public always made him a betting favorite, even though he’d be riding a goat.”

In his first year of riding in Russia, James Winkfield won the Russian National Championship in 1904, ironically, from another American, white jockey Joe Pigott. Winkfield also won all of the three big Russian Derbies – the Moscow, the Warsaw, and the St. Petersburg Derby, described by Hotaling as a kind of “Czarist Triple Crown.” Hotaling quotes a Russian commentator visiting America during that time as saying that the American jockeys, including Winkfield, “have earned salaries in Russian beyond their fondest hopes.”

1909 – Winkfield in Russia, Germany, and Austria

All over Europe, James Winkfield was the first-call rider for nobilities as a German Baron and a Polish Prince. Not only did he earn 10% of all purses he won, but he was receiving 25,000 rubles a year. At one point was earning 100,000 rubles a year.

Winkfield eventually left his long-time collaborator Michael Lazareff and went to Austria to ride for a Polish prince and then to Germany to ride for a German baron. In Germany, he won the ‘Grosser Preis von Baden,’ worth a hundred thousand marks, and he soon became a big factor in German betting operations (the odds). He would later recount his story of riding for the baron in his Sports Illustrated piece with Roy Terrell.

One day Wink said he decided that he wanted to ride one of the baron’s colts that no one thought could run, so he talked to the baron about riding the colt. “I was getting pretty famous over there by then, and the baron said no. If I ride him, the people would bet on me and lose their money.”

But the Baron eventually yielded allowed Winkfield to ride the colt. He was stuck on the difficult colt at the start while the other horses were fifteen lengths up the track. “Then we get to the stretch, and I give him a cluck or two, and off we go,” Winkfield said. “He ran so fast the others never see us coming. We won by eight lengths.”

James Winkfield Living Large In Russia

He’s with the horses

James Winkfield’s sister Maggie’s – Testifying to Wink’s whereabouts in his dovorce proceedings

In 1911, his wife sued for divorce, citing abandonment, which Winkfield did not contest. When a lawyer asked her where her brother was, Winkfield’s sister Maggie, testifying in the case, gave a simple answer, “He’s with the horses,” she said.

James Winkfield had gotten over the racism in American and his forced exit for greener pastures by “getting even.” In Russia, he was living large. In 1913, he went back to Russia to work with another Armenian, Leon Mantacheff, for a salary of twenty thousand rubles plus ten percent of all purses. He took a suite at the National Hotel in Moscow (then equivalent to Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria), hired a valet, and had caviar for breakfast each morning. “I was at the top of a tree,” Wink said.

He had other American colleagues and friends in Russia – mostly white jockeys who would keep him abreast of what was happening back home. The news he got was that as a result of the shutdowns of racetracks across America, many white jockeys were fleeing in search of greener pastures in Europe. As for the black jockeys, Winkfield got the news that they were a thing of the past – driven out of the sport.

American racing had gone from 314 racetracks to 25 by 1908, with most of the major New York venues at the center of racing legislated out of business. While James Winkfield was exploding on the Russian stage, his white counterparts in America struggled to find mounts, and his black colleagues, no longer a factor in the sport.

So well did he succeed in Russia with his new collaborator Montacheff, that Winkfield later told Sports Illustrated that, “We sure won a lot of races… I won 130 one year, riding only three times a week.” If we allocate, say, six out of fifty-two weeks for vacation or holidays (a rough guess), Winkfield’s winning percentage would be an astounding 94 percent. It might have been even higher depending on the length of the racing season.

James “Wink” Winkfield had indeed made the right decision to flee America. Wink was the Bricktop, the Eugene Bullard, the Josephine Baker, the Sydney Bechet, and the Henry Ossawa Tanner of horseracing. They all had their Paris, but James Winkfield had his Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Czar Nicholas II – A Winkfield Fan But A Cheapskate

James Winkfield was living and racing in imperial Russia when the last Czar Nicholas II was the Head of State. Winkfield said he opted not to work for Czar Nicholas II because the Czar kept 25 percent of his winnings and gave the rest to the second horse’s owner. According to Winkfield, “he [the Czar] never paid his jockeys nothing. Maybe 4,000 rubles, so I never rode for him.”

But the Czar, with a passion for racing, was one of Winkfield’s biggest fans, who often showed up at the track to watch Wink race. According to Winkfield, “Before the revolution, that was a good country. And I never had to pay no income tax.” But the Bolsheviks would arrive, and their arrival would force James Winkfield to flee Russia – the country in which he had accomplished so much and in which he had had such a good life.

James Winkfield’s achievements in Russia include winning Russian Champion Jockey three times, winning the Russian Oaks five times, the Russian Derby four times, the Czar’s Purse three times, the Warsaw Derby twice, and once winning the “Czarist Triple Crown”—the Moscow Derby, St. Petersburg Derby, and Warsaw Derby.

Arrival of Bolsheviks

When the Communist Revolution came, James Winkfield described the Russians as “like rabbits in the woods. They did not know which way to go.” As would be expected, the Bolsheviks allowed the tracks to stay open and paid no attention to the people there. A revolution needs people on its side, and it would be unlikely to co-opt populist sentiments by closing their beloved sport. However, one of those involved in the sport was an African American capitalist who was earning upwards of an equivalent hundred thousand dollars annually.

Winkfield recounted his survival tactics during the revolution to writer Terrell as follows: “Nobody bothered us so long as we stayed dirty and wore old clothes. But if we ever dressed up, they would have figured we were aristocrats.” No doubt he had by then ditched both valet and hotel suite and would have likely had to procure his morning caviar in underground markets, discretely consumed.

Winkfield Flees Russia – Via Odessa

The time did come when James Winkfield had to escape Russia and the Bolsheviks. The Moscow Jockey Club had run out of money, and they had shipped all their horses to the Black Sea resort of Odessa, which was a natural haunt of the Russian aristocracy, so it soon became an even more dangerous place to be than Moscow.

With revolution troops on the edge of the city in April 1919, James Winkfield recalled telling himself, “This ain’t no longer a fit place for a small colored man from Chilesburg, Kentucky, to be.” He assumed responsibility for moving the entire racing operations, inclusive of jockeys, women, and children, along with some two hundred thoroughbreds. Along with a Polish nobleman, the group headed south first towards Romania.

Winkfield described it as “quite a trip.” Villagers often fired upon them, thinking they were Bolshevik agitators. Others refused to give them food, thinking they were gypsies (a small black man, a sight never before seen, would have certainly given cause to believe that they were gypsies).

And then there was the issue of timing and cultural practices. According to Winkfield, “Once… we came upon this cow. But it was Lent, and no one would eat her. We drive her along for 20 or 30 miles, trying to get her to Easter. We finally swapped her for a pig and ate him on Easter Sunday.” In other words, Winkfield and his group had to “run out” Lent to be able to eat a piece of meat in that Orthodox region of the world.

Winkfield and Company Arrives in Bucharest, Romania

In the Romanian capital, they put the women and children on a train bound for the Polish capital, Warsaw, and then the men and horses were off again. With the horses, they traversed the Transylvanian Alps and across a patch of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Some of the horses starved to death on the trip, while the travel party ate some of the others to stay alive.

The journey to Warsaw was a thousand miles and took two months to travel from Odessa. On arrival in the Polish capital, only 150 of the original 200 horses remained. Winkfield said that none ever raced again and that they were all eaten that winter. In Warsaw, James Winkfield would resume riding, including once before a vising American VIP – Herbert Hoover.

With the onset of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, James Winkfield fled to France, where he continued to race for another decade, retiring in 1930 with 2,600 career wins. When the Nazis entered France, they seized his farm in 1940, forcing him to flee back to the United States, where he could only find work on a WPA work crew.

A Return to the Past

By 1953 James Winkfield was back in France, where he opened a training school for jockeys. Back in the United States in 1961, six decades after winning his first race at the Derby, Sports Illustrated him to the National Turf Writers Convention‘s pre-banquet event at the Kentucky Derby at Louisville’s historic Brown Hotel. The man whose riding skills had gained him fame, fortune, and appreciation beyond his dreams in Czarist Russia, along with his daughter Liliane, were denied entry to a venue he had made legendary – because they were African American. After a long wait and much explanation and proof offered that they were Sports Illustrated’s guests, they were finally admitted.

End of a Journey

The era of greatness for African American jockeys at the Kentucky Derby had ended with two-time winner James “Wink” Winkfield’s 1901 and 1902 wins. But that did not stop him. After racism forced him from the race and his country, Wink left the United States made a name for himself in Czarist Russia, France, and elsewhere across Europe.

James Winkfield died in France in 1974, age 91. He was honored in 1995, on the occasion of the 131st Derby, with a Congressional House Resolution. Among James Winkfield’s footprint left in Russia, we know of his son George, born into Russian nobility to Winkfield’s wife, baroness Alexandra Yalovicina – a fitting plunge for the caviar-eating playboy who once lived at the National Hotel in Moscow with a hired valet at his disposal.

If you like this story, please subscribe and share, if possible

Sources:

Edward Hotaling’s The Black Jockeys

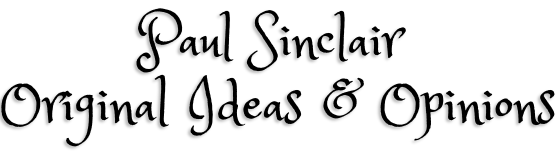

Catherine C. Mooney’s Race Horse Men

Harvard University Press’ Slavery and Freedom at the Racetrack

Blinker Biases’ Horse History, and Humor